He grew up at Bekkestua and entered the youth department of Stabæk at the age of five.

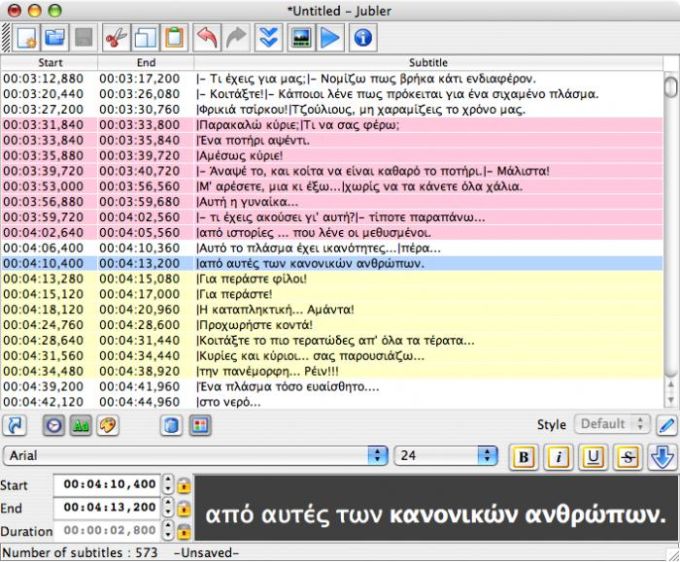

#Jubler pdf professional#

Tobias Borchgrevink Børkeeiet (born 18 April 1999) is a Norwegian professional footballer who plays as midfielder for the Eliteserien club Rosenborg. ‡ National team caps and goals, correct as of 10 August 2021 In short, I think we can all expect more scraping and content-stealing - and IT will sadly find that it really can't do much to stop it.*Club domestic league appearances and goals, correct as of But the coder who posted it has no course of action. The only legal action is that their companies could fire them for disclosing internal information.

Why? Because we know that a lot of coders and other technical talent will massively overshare, detailing what they did on projects for their employer, including lots of highly sensitive information about the systems they worked on, applications their employer purchased, and even unannounced security holes they fixed. One of the more interesting uses journalists have with LinkedIn is reviewing the details of someone’s experience. If I post something sensitive about myself in a public forum on a large discussion site, do I have a reason to expect privacy? (Actually, I might because no one cares what I think, but I digress.) If I had wanted something kept quiet, I wouldn’t have publicly posted it. This is where we get into the public space argument. Does anyone challenge my right to do so?Īnd where exactly should the line be drawn on what constitutes scraping? Is referencing one title scraping? How about four prior titles from one person, or 10? Or if it's information on more than 100 people? That’s a problem, because if LinkedIn decides to not worry about small data references, it undermines its ability to pursue the big ones. However, do users expect material they post on LinkedIn to appear only on LinkedIn? More to the point, do those users have any realistic expectations that it will stay put? I, like a lot of reporters, have often gone to a LinkedIn page to check on biographical information from or a source or double-check a person's professional background info for a column or post I'm writing. If LinkedIn paid me to post comments and messages and work history details, then maybe it could argue ownership. Can LinkedIn even argue with a straight face that it legitimately owns all of the information in my resume, which I posted on my page on LinkedIn? The overwhelming amount of content being scraped involves what LinkedIn customers individually write for free. Unlike a media outlet (such as "Computerworld") LinkedIn doesn’t pay money to create excellent content. LinkedIn’s particulars make that argument tough. A better - though perhaps equally unlikely-to-win–argument - would be copyright violations. Getting back to the LinkedIn case, I would argue that even citing The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act was a massive and wrong-headed argument from LinkedIn. And most web people will quickly conclude that just accepting the scrapers is probably the best call.

That dilemma is similar to fighting scraping efforts. (And our fears were confirmed PDFs of our premium content started appearing all over the place.) After quite a few subscribers threatened to cancel their paid subscriptions, we surrendered and reinstated the ability to print.

#Jubler pdf pdf#

(Saving as PDF is really printing to PDF, so blocking PDF downloads meant blocking all printers.) It took just a couple of hours before new premium subscribers screamed that they paid for access and they need to be able to print pages and read them at home or on a train. But that meant that those pages also couldn’t be printed. That meant that we blocked cut-and-paste and specifically blocked someone from saving the page as a PDF. We couldn’t allow people to freely share premium content, as we needed people to buy those subscriptions. Years ago, I was managing a media outlet that was making a huge move to premium content, meaning that readers would now have to pay for selected premium stories.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)